Title photo shows the Kanakakkunnu afforestation project in an urban forest in the heart of Thiruvananthapuram city in India. Around 420 indigenous wild trees, medicinal trees and plant saplings have been planted in an area not previously forested.

Afforestation is establishing a forest, especially on land not previously forested. It remains one of the most effective means of tackling climate change since trees act as a CO2 sink, taking up the gas for photosynthesis. Afforestation can also improve the local climate through increased rainfall and by being a barrier against high winds. The additional trees can also prevent or reduce topsoil erosion (from water and wind), floods and landslides. Finally, additional trees can be a habitat for wildlife, and provide employment and wood products.

Recently, the UN Food and Agriculture Organization estimated that 100 billion square meters of forest were cut down each year over the last decade, while tropical deforestation has contributed 8 percent of global carbon emissions.

Research from Crowther Lab, an interdisciplinary team of scientists studying climate change, showed that one trillion new trees could absorb one-third of CO2 emissions made by humans. In fact, an additional 25 percent of forested area could absorb 25 percent atmospheric carbon, making a huge impact on rising temperatures globally.

If afforestation is going to reach these levels of planting, then it will need an international commitment involving governments, the private sector and local communities. One trillion trees would require 900 million hectares of suitable land, with soil containing sufficient nutrients and moisture, capable of sustaining the growth of tree seedlings to maturity.

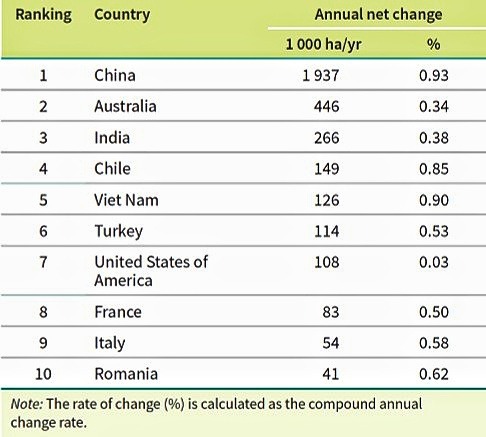

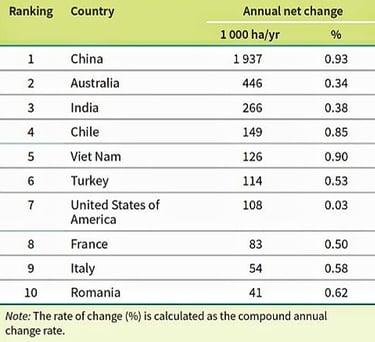

Figure 1 lists the top ten countries for average annual net gain in forest area from 2010 to 2020.

Figure 1

UN FAO data

While these countries were engaged in afforestation projects, deforestation across the world was taking place on a far greater scale, resulting in a colossal net loss of forest. Between 2010 and 2020, this net loss amounted to 4.7 million hectares per year. China's net gain over the same time period (see table 1) of 1.937 million ha/yr is cancelled out by deforestation, the vast majority of it in tropical forests.

The global picture since 2020 is showing signs of becoming less grim although the pace of change is far below what is needed if forests are going to rescue us from +3C.

Despite the renewed enthusiasm for planting trees across the world and the pressure on countries with large tropical forests to curb deforestation, for a number of countries, afforestation is proving a far bigger challenge than cutting emissions from fossil fuels. The UK will serve as an excellent example of a government promising much and delivering little.

For a complex mix of reasons, UK tree-planting targets have been missed year-on-year ever since the Conservatives took office in 2019. That year, the UK Climate Change Committee (CCC) which advises the government on necessary policies required to reach net zero by 2050, declared that tree-planting targets would have to be increased in the UK to 30,000 hectares annually by 2025, and then raising it still further up to 50,000 hectares by 2035. If this was sustained annually, then by 2050 UK forest cover would have increased from 13% in 2019 to 18% by 2050 and in the process have removed 10MtCO2 from the atmosphere each year.

But 2025 has arrived and 30,000 hectares of planted woodland has never happened. In each of 2020, '21, '22, and '23, a mere 13,000 hectares of afforestation took place in the UK. This increased to 20,000 in 2024, still far short of the CCC's target. A highly critical report released by MPs on the Environmental Audit Committee in 2023 stated: “We are extremely concerned by the consistently poor progress made in increasing tree-planting rates across all four of the nations in the UK.”

Then yet another General Election came around in 2024 full of vague promises in manifestoes. We'll plant "millions of trees" said Labour. "We'll deliver existing commitments" said the Conservatives. Neither party had a clear roadmap of how they would reach 30,000 hectares of planting, upscaling to 50,000 by 2035.

The underlying reasons for the lack of planting are complex but boil down to these:

complex bureaucratic processes for landowners to navigate before planting schemes can begin;

lack of clear incentives for the private sector to engage in large scale planting;

lack of skilled arborists to manage large scale planting;

lack of tree seedlings grown in the UK.

UK governments have pinned their hopes, like many countries around the world, on afforestation projects acting to offset the carbon emissions that are too painful to eliminate by 2050. Aviation, agriculture, industry. But without planting trees now, there is little chance of that happening. Tree seedlings take time to grow to a size where they begin maximum photosynthesis, 'sucking' CO2 from the air. Afforestation in the UK will need to greatly exceed 50,000 hectares every year until 2050 to offset the unavoidable (?) carbon emissions and so achieve net zero.

And that sums up the position globally. There is still too much deforestation stealing the progress from afforestation. The offsetting of global emissions from fossil fuel power stations - coal in particular - will require the World Economic Forum's '1 trillion trees planted' target to be fully met well before 2050.

Watch this space.

The World Economic Forum reported back in 2021 that around the world, governments, the private sector, and local communities had started work on some promising projects. How did this sudden enthusiasm for afforestation come about? In 2021, the COP26 climate conference in Glasgow gave new impetus to forest conservation worldwide. Signatories to the Glasgow declaration on forest and land use committed to “halt and reverse” forest loss and land degradation by 2030, while at the same time “delivering sustainable development and promoting an inclusive rural transformation.” The 141 countries that signed up contain 90% of global forest coverage.

The problem is that so many commitments to curb deforestation have come to nothing. In 2014, the New York Declaration on Forests aimed to cut deforestation in half by 2020, and end it by 2030. But a 2020 progress report showed the problem had only worsened since 2014. Are the promises made in Glasgow being realised?

One of the promising projects mentioned above, the 1t.org, has set out to restore and grow one trillion trees by 2030. They are working in countries around the world including China whose 14th Five-Year Plan for the Protection and Development of Forests and Grasslands states that: "by 2025, China will complete the goal of greening approximately 33.3 million ha of land area, thereby increasing the country’s forest coverage rate to 24.1%." At the World Economic Forum’s 2022 Annual Meeting, China’s Special Envoy for Climate Change announced that further action will be taken in.....forest carbon sinks, strengthening the conservation of existing forests, and striving to plant and conserve 70 billion trees within 10 years in response to the 1t.org initiative.

70 billion - that's 7% of 1 trillion. By 2032. China is a very large country but still, 70 billion trees?