F L O O D S

Flooding in Porto Alegre of the Lagoa dos Patos in Brazil during May 2024

The science behind the link between climate change and the increased frequency and intensity of heavy rainfall couldn't be simpler. Warmer air can hold more moisture, 7% more for every 1 degree rise. Warm air moving across an ocean has an unlimited water supply and draws up extra moisture. The resulting clouds contain vast quantities of water. When the clouds reach land and are pushed up into the colder atmosphere, they can no longer hold their load of water which condenses into droplets and falls as rain. Torrential rain. As the climate continues to warm, this effect will increase, and heavy rainfall events will almost certainly become more common.

In this section, we'll look at flash floods - the result of intense rainfall over a short period - and river floods caused by persistent rainfall over a longer period. Both are forecast to become more common as the Earth's temperature rises.

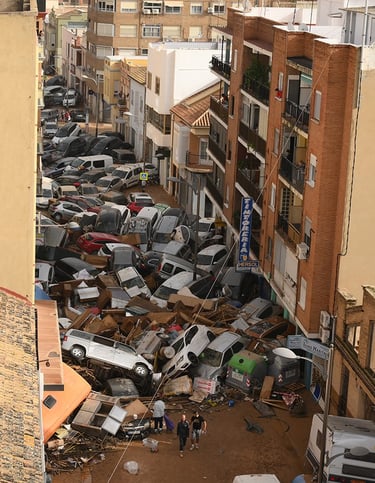

On 25 October 2024, the Spanish national meteorological agency AEMET issued a warning of an upcoming storm in eastern Spain, notably the Valencia, Castilla and Andalusia regions. This was immediately ridiculed on the social media platform X by climate change denialists.

Four days later, on 29th October, all hell broke loose as torrential rain fell across the region. At 07:36, AEMET issued a red warning for the Valencia area. By 10:30, emergency services were rescuing people from cars in the town of Ribera. At 11:30, a ravine running through Chiva overflowed and flooded the town. By the end of the day, over half a meter of rain - over a year's worth - had fallen there. At 12:00 the Magro River burst its banks and flooded Utiel. The mayor there reported water levels three meters deep. At 18:00 the town of Turis recorded 42mm of rain in 10 minutes and set the new Spanish record with 184.6mm in just one hour. At 18:30, the River Poyo burst its banks in Torrent and flooded downstream through a number of towns in Horta Sud.

q

The photo above shows a street in the Valencia suburb of Sedavi. 230 people tragically lost ther lives. The degree of destruction and ruin was historic in the Valencia region where 80 towns were deluged by torrential rain. All this poses a critical question: Did climate change play a role in this flash flooding?

The October floods can be attributed to four factors which combined to create the sheer scale of the tragedy.

Geographical location: The city of Valencia, like so many of the world's cities, lies around a riverbed on a flat, alluvial coastal plain. The city centre was well protected from flooding owing to the obvious risk posed by the river Turia running through the centre. However, the surrounding peripheral municipalities such as Sedavi and Paiporta were not protected and became inundated very quickly.

Urbanisation: From 1997 - 2007, there was intense urbanisation of the areas around the city of Valencia, vastly increasing the area of impervious land where water cannot soak away during heavy rain.

Spain's central highlands: Heading inland from Valencia, the landscape quickly gains altitude. Warm air laden with moisture from the Mediterranean is swept inland and pushed up by these hills and cools. Cold air cannot hold as much water so the water vapour condenses and it rains. This phenomenon is called Cold Drop. In 1957, a similar disaster overtook the city as a result of a torrential inland cold drop. Action was taken thereafter to protect the city centre but plans to protect the areas to the south were shelved.

Climate change: For every 1 degree Celsius rise in temperature, air can carry an additional 7% water vapour. The warmer the air, the wetter it can become. An Extreme Weather Attribution study was carried out immediately after the event by the World Weather Attribution initiative. Their results indicate that as a result of the increased temperature caused by greenhouse gases, the Valencia floods were 12% more intense and twice as likely to happen in today's climate as in the pre-industrial period.

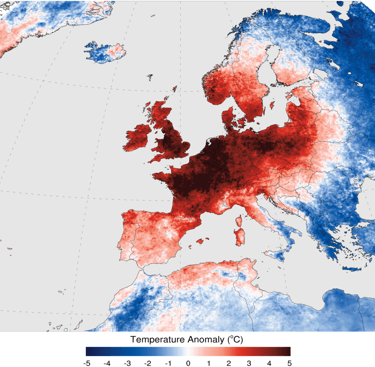

The 2024 Spanish floods are sadly not an isolated event in the 21st century. In July 2021, widespread flooding occurred across Europe due to a slow-moving low pressure system (see photo below) travelling from a warmer-than-average Baltic Sea. This loaded the air with very high levels of moisture.

By NASA - https://worldview.earthdata.nasa.gov/,

Figure 1

Figure 2

As a result, extreme flooding occurred in parts of Belgium, Germany and surrounding countries. Record precipitation amounts were observed in the affected areas on 14 July 2021. At least 243 people died in these floods. In the days and weeks following the floods, climate scientists across Europe and America were adamant that climate change had played a part. Antonio Navarra, climatologist at the University of Bologna and president of the Euro-Mediterranean Center Foundation on Climate Change, said that there is a clear correlation between the increase in the concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere and the frequency and intensity of floods, heat waves and drought periods. Carl-FriCreedrich Schleussner of Humboldt-Universität Berlin said the question was not whether climate change had contributed to the European floods, but rather "how much".

While US and European media have been focussed on the extreme floods and fires across the two continents in the 21st Century, the events taking place in Amazonia have largely gone under the radar. Manaus is the capital and largest city (over 2 million inhabitants) in the Brazilian state of Amazonas. It sits in the Amazon rainforest at the junction of two huge rivers, the Negro and Amazon (see Fig 3 below).

Figure 4

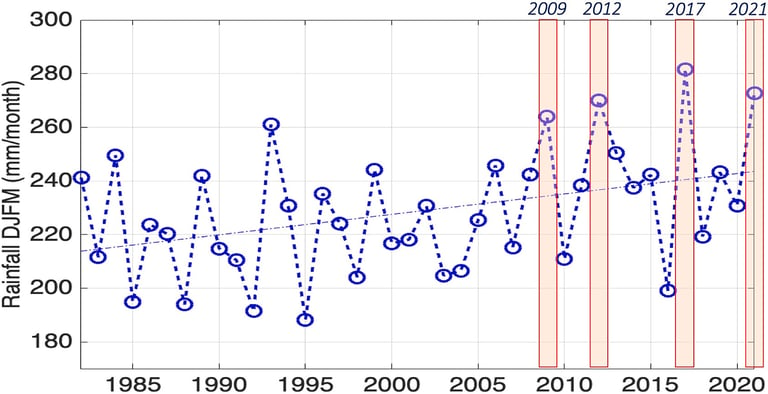

When river levels at the confluence rise above 29m, a critical emergency is triggered by the Manaus authorities. During the period 1903–2008 (106 years), the total number of emergency days was 400. During the last 13 years (since the 2009) the total number of such days was 475. Of the 10 highest annual water levels recorded at Manaus during the last 119 years, five occurred during the last 10 years (2021, 2012, 2015, 2014 and 2019), including the two biggest flood events: 2012 and recently in 2021.

To understand the forces behind these recent floods, we need to look at rainfall across the whole of Amazonia, both north where the flooding occurred and south where deforestation has reduced annual rainfall totals.

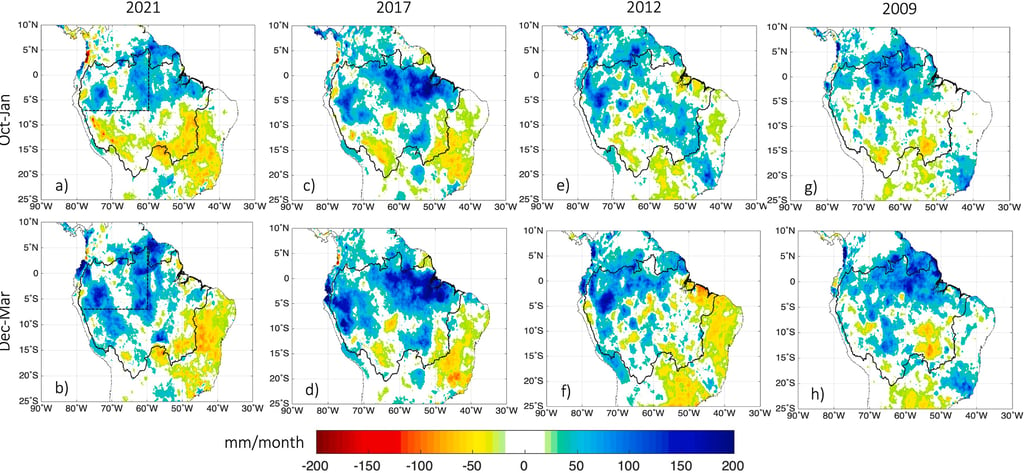

Jhan-Carlo Espinoza, José Antonio Marengo, Jochen Schongart, Juan Carlos Jimenez; The new historical flood of 2021 in the Amazon River compared to major floods of the 21st century:

Figure 5

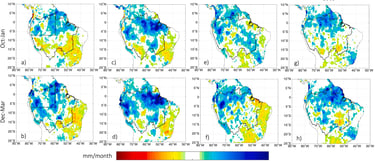

The 8 charts in Figure 5 are worth studying for a few moments. They portray a developing catastrophe for northern Amazonia. Displayed in the charts is the northern half of the South American continent. The extent of the Amazon catchment is outlined in black. The rainfall anomalies compared to the 1982-2020 average in this catchment area are displayed in two seasons (Oct-Jan and Dec-Mar) for 2009, 2012, 2017, and 2021. Dec-May is the wet season and more rain is therefore expected in these months. But any blue/dark blue on the maps indicates rainfall well above the 1982-2020 average. The rain falling in northwest Amazonia is funnelled into the Rivers Negro and Amazon. And year on year, it's increasing in volume.

Figure 6

(Image source as Fig 5) 1982–2021 rainfall variability during the December–March season averaged over the northwestern Amazon Basin. Vertical red bars indicate extreme flood years associated with rainfall over the western Amazon. Linear trend is indicated with a dotted blue line.

But we're not done with the Fig 5 charts. Look at south-eastern Amazonia. Worrying patches of yellow and orange appear at some point in each of the four years. The data suggests that in southern Amazonia, loss of forest is reducing rainfall. This was discussed in the deforestation page. The northern pattern of rainfall in Amazonia is also extremely concerning since it is leading to prolonged and severe flooding which destroys crops and pastures, contaminates water supplies, and cuts people off from their homes for weeks or even months at a time. In June 2021 a new historical record flood was reported in the Amazon Basin, surpassing the once-in-a-century flood of 2012. This new flood produced an emergency situation at Manaus for 91 days, at the same time as the COVID-19 health and medical emergency. The water level at Port of Manaus reached 30.02 m, surpassing even the previous historical flood of 2012 of 29.97 m.

Increasingly heavy rain and floods in the Amazon are linked to atmospheric changes caused in part by ocean warming linked to climate change, said Jochen Schoengart, a researcher with the National Institute for Amazonian Research.

During the first 70 years of water level measurements at the port in Manaus, a big flood was recorded every 20 years, said Schoengart, who specializes in the history of hydrological cycles and forest floods.

But "in the last 10 years, we have seen seven major floods. And among those big seven, we have the two biggest on record, in 2012 and now in 2021," he said.

"At the same time," writes Fabio Zuker in PreventionWeb, "parts of southern and west-central Brazil in the Paraná River basin - including Brazil's largest city of Sao Paulo - have suffered unprecedented drought due to low rainfall.

The disastrous mix of floods, drought and intense downpours could be a glimpse of a potentially dire future as a heating planet and surging deforestation alter long-standing weather patterns throughout Brazil and South America, scientists warn."

Title photo By Lula Oficial - https://www.flickr.com/photos/lulaoficial/53700500641/, CC BY-SA 2.0,