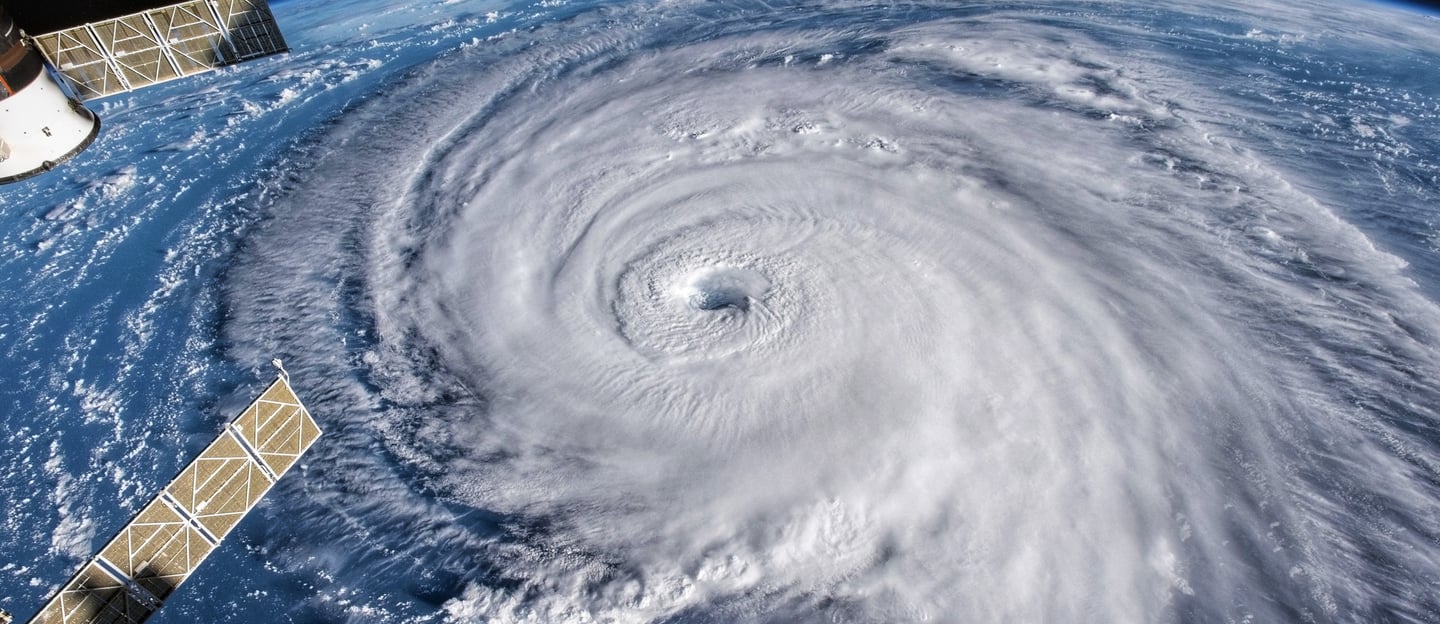

The title photo, taken from the International Space Station, shows Hurricane Florence approaching North Carolina in the US, where it caused 30 inches of rain to fall, resulting in catastrophic flooding.

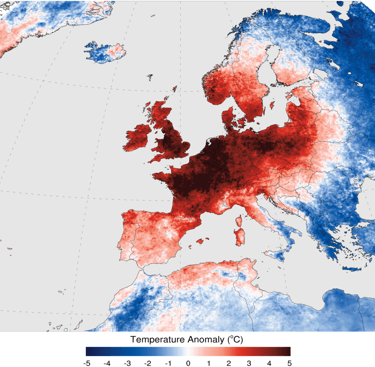

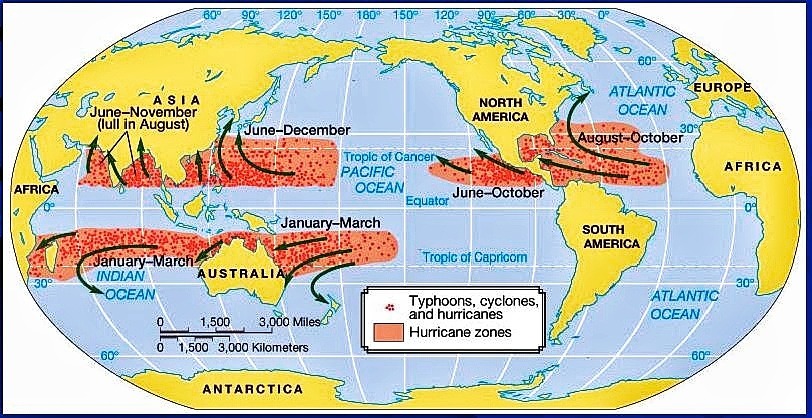

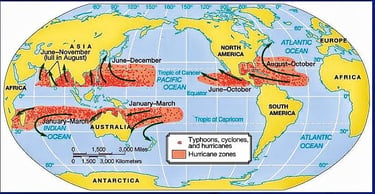

‘Tropical cyclones’ is a collective term for hurricanes, cyclones and typhoons. There is no compelling evidence to suggest that these have increased in frequency over the last hundred years. But according to the IPCC (inter-governmental panel on climate change), it is likely that a higher proportion of tropical cyclones across the globe are reaching Category three or above. On the Saffir-Simpson hurricane scale, 111-129mph winds rate category 3, 130-156mph is category 4. Anything above that, category 5. The UK’s extratropical Great Storm of 1987 would have registered category 3 on the S-S scale. I cannot imagine the devastation caused by categories 4 and 5 and yet those living in the world’s hurricane zones (see Fig 1) are increasingly at risk of such storms.

Climatology of tropical cyclone occurrences. Courtesy of the University of Hawaii. Cristiano Pesaresi

Figure 1

When Hurricane Katrina approached the US coast in 2005, it generated a storm surge of more than 8 metres in some areas. This led to widespread flooding, including almost all of the city of New Orleans where the sea defences couldn't cope with the water level. More than 1800 people were killed across the US by Hurricane Katrina, many of them by the storm surge flooding.

How then does a warming atmosphere increase the height of a storm surge? Firstly, and most obviously, through rising sea levels. Melting glaciers, ice sheets and expansion of water as it warms is slowly but inexorably raising sea level. Add to this the hurricane’s low pressure and you have the recipe for catastrophic coastal flooding. Secondly, hurricane winds are increasing in strength due to the energy gained from warmer waters, and apply greater force on coastal water as the hurricane approaches landfall.

The warming atmosphere may not be increasing the frequency of tropical cyclones but once formed, there is a growing body of evidence that warming oceans are increasing their destructive potential.

The IPCC believes with ‘medium confidence’ that peak rainfall rates and the average rainfall associated with tropical cyclones has increased. They also believe that the rate at which wind speeds increase during a storm has increased, a process called rapid intensification. This gives communities little time to prepare their homes and dependents for the oncoming winds and rain.

There also seems to have been a slowdown in the speed at which tropical cyclones move. This brings more rainfall for a given location. In 2017 Hurricane Harvey "stalled" over Houston, releasing 100cm of rain in three days. See Fig. 2.

How do rising temperatures affect tropical cyclones? Over the last 50 years, most of the land surface has warmed by between 1 and 2 degrees. But the ocean surface has also warmed, between 0.5 and 1 degree. Warmer ocean waters mean storms can pick up more energy, leading to higher wind speeds. Moreover, warmer air can hold more moisture. This leads to increased rainfall.

Coastal communities living in hurricane zones face a further deadly threat – storm surges. The atmospheric pressure in the centre of a hurricane is extremely low. When air pressure falls, the sea level rises. If a hurricane reaches landfall during a spring high tide (a tide occurring at a new or full moon), then, with the added force of extremely high winds, sea levels can rise catastrophically. Such an event occurred on November 12, 1970 when the Bhola cyclone struck present-day Bangladesh and India’s West Bengal (Fig. 3). At least 300,000 people died principally as a result of a 10 meter storm surge that tore across the low-lying islands of the vast Ganges Delta.

Figure 3 - The Bhola Cyclone

Figure 2 - Hurricane Harvey

Title photo by NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center - Dramatic Views of Hurricane Florence from the International Space Station