N I T R O U S O X I D E

By Chafer Machinery

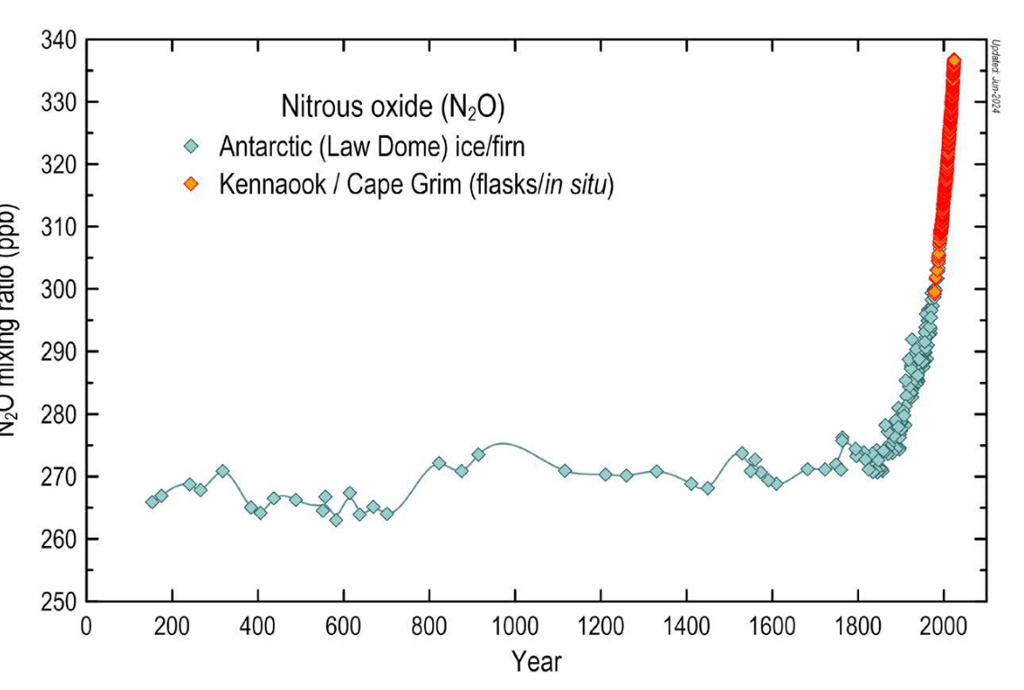

David Kanter, a nutrient pollution researcher at New York University, calls nitrous oxide (N2O) the forgotten greenhouse gas. Like methane, it’s present in tiny amounts in the atmosphere - 336.7ppb in 2023 - but N2O has a global warming potential 273 times that of carbon dioxide, far greater than methane. For 800,000 years, nitrous oxide concentration rarely exceeded 270ppb. With the advent of the industrial revolution, it followed the same pattern as CO2 and methane, rising ever more rapidly throughout the 20th Century.

Tian, H., Xu, R., Canadell, J.G. et al. A comprehensive quantification of global nitrous oxide sources and sinks. Nature 586, 248–256 (2020).

Figure 1

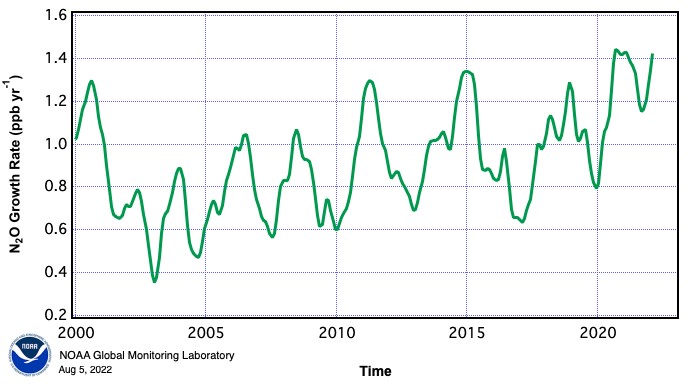

Now in the 21st Century, that year on year increase in the rate of N2O emissions continues to rise.

Figure 2

About 40% of N2O emissions are from human activity and the rest are part of the natural nitrogen cycle. The N2O emitted each year by humans has a greenhouse effect equivalent to about 3 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide. This compares with 37 billion tonnes of actual CO2 in 2023, and methane equivalent to 9 billion tonnes of CO2. What is deeply concerning is the year on year rise of atmospheric nitrous oxide. So how exactly is man creating such vast quantities of this gas, and can this be stopped or at least reduced?

Almost all of anthropogenic nitrous oxide comes from agriculture. It is estimated that a third of annual global food production uses 100 million tonnes of synthetic nitrogen-containing fertiliser each year and that this supports nearly half the world's population. There is little doubt that the development of synthetic nitrogen fertilizers has significantly supported global population growth. But this comes at an environmental cost – nitrous oxide.

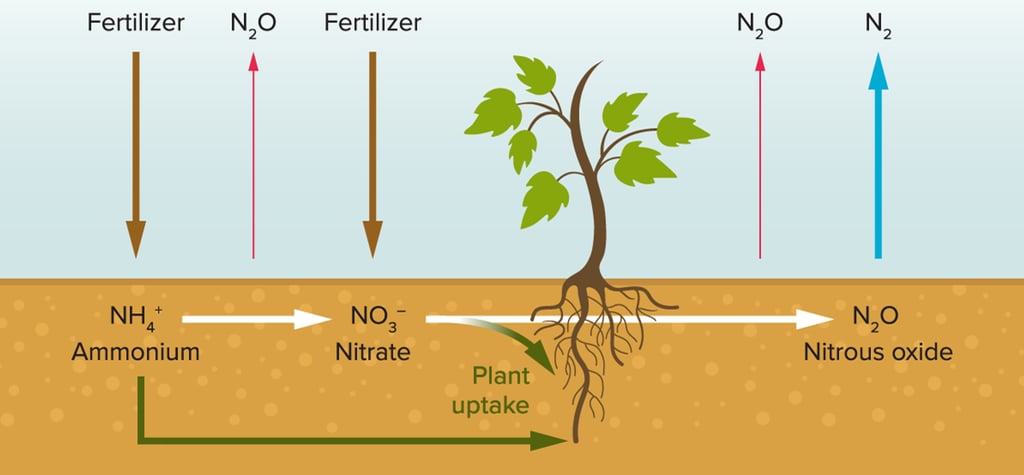

When fertiliser containing ammonium (NH4+) is added to the soil, some of it is taken up by the crop plants. Some of it is converted into nitrate (NO3-) by bacteria, a process which releases nitrous oxide into the atmosphere. Again, some of the nitrate is taken up by the crop plants. Both ammonium and nitrate stimulate the growth of the plant and have a considerable impact on crop yield. But crop plants cannot access all of the fertiliser added to the soil. In fact, somewhere between 30% and 70% remains in the soil or is washed away by rain (runoff) and undergoes a process known as denitrification which once again releases nitrous oxide into the atmosphere. Given the sheer scale of fertiliser use, it’s no wonder that atmospheric nitrous oxide is on the rise

Given agriculture's dependence on fertilisers, reducing N2O emissions is going to be a challenge but, like CO2 and CH4, it is critical that technology finds a way to sustain crop yields without artificial fertiliser.

Figure 3

Credit: E. Verhoeven et al/California Agriculture 2017/Knowable Magazine