Title photo: Built in 2020, the electric powered NXTE was developed from the Sharp Nemesis NXT and is supported and operated by Rolls-Royce as the ACCEL (ACCelerating the ELectrification of flight). It first flew on 15th September 2021 and set the world airspeed record for an electric aircraft on 19th November 2021, reaching 345.4mph whilst piloted by Steve Jones.

11.6% of the 9.98 billion tonnes of CO2 emitted into the atmosphere by all forms of transport last year were the result of aviation. That's 1.16 billion tonnes. 1,160,000,000 tonnes. [A tonne of CO2? Isn't CO2 a gas? How can it weigh anything? But it does. Imagine a cube made of telegraph poles - one pole high, one wide, one long. If you fill the cube with CO2, you'll need one tonne of the gas.]

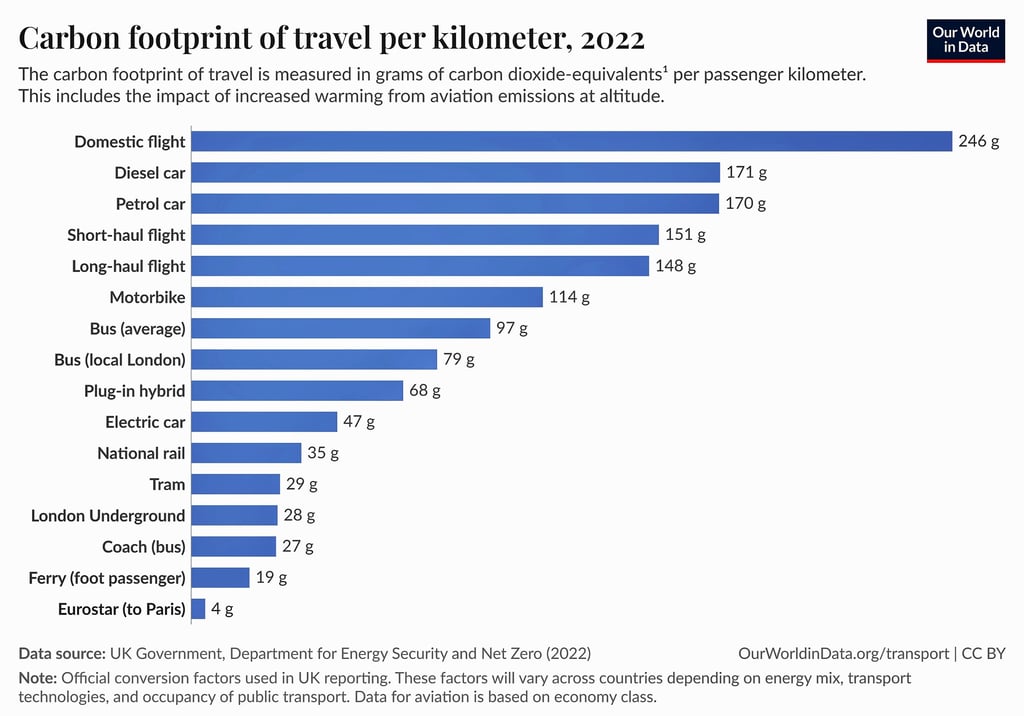

Of that 1.16 billion tonnes, 940 million tonnes came from passenger aircraft and 22 million came from freight aircraft. Fig. 1 is a reminder of the carbon emissions - 'footprint' - for each km travelled by each passenger on different duration flights. So if you flew from London Heathrow to New York, a distance of 5,570km, then your carbon footprint would be 148g x 5,570 = 824,360g or 824kg. That's approaching a tonne. Look around the cabin. There are 300 other passengers, making total CO2 emissions of 247 tonnes.

Figure 1

How, then, can the carbon emissions from aviation be reduced? Is electrification of passenger aircraft a realistic prospect in the near future?

The primary problem facing the electrification of aviation is the low energy density of current battery technology, which significantly limits the range of electric aircraft due to the heavy weight of batteries needed to store enough power for long flights. Other challenges include power distribution, cooling systems, and integrating electric propulsion systems into existing aircraft designs, all while maintaining weight limitations and safety standards.

Progress towards electrification of passenger planes will come in three stages: more electric hybrid, full hybrid and then all electric. The projected future of manned electric aircraft looks something like:

Near term (next few years): Small electric aircraft for short-range flights are expected to enter commercial service.

Mid-term (2030s): Hybrid-electric regional aircraft could become more prevalent.

Long-term (beyond 2040): Large, fully electric commercial aircraft may become viable with significant advancements in battery technology.

Heart Aerospace are a Swedish-based start-up working on a 19-seat electric plane which started testing in 2024. It carries 3.5 tonnes of batteries (!) with a claimed range of 250 miles. The problem facing small electric planes like this is the Reserve Requirements, i.e. a plane needs extra capacity to circle the airport for 30 minutes in case it can’t land right away, and it must also be able to reach an alternative airport 100 km (60 miles) away in an emergency. Even with a doubling of battery energy density - that's about the limit for lithium-ion technology - electric aircraft would only displace enough aircraft to cut aviation emissions by 1% by 2050. The big polluters are, predictably, the big passenger jets and their electrification will happen too late to stop +3°C. Meanwhile, other technologies like alternative fuels and green hydrogen have much higher energy densities, so they’re a more likely candidate for longer flights, provided that they can be produced economically at scale.

If electrification is not the answer, what is? Part of the solution may be Sustainable Aviation Fuels. SAFs are liquid fuels currently used in commercial aviation, which can reduce CO2 emissions by up to 80%. It can be produced from a number of sources (feedstock) including waste fats, oils and greases, municipal solid waste, agricultural and forestry residues, wet wastes, as well as non-food crops cultivated on marginal land. The challenge facing SAFs is simply scale - the sheer volume required to make a significant dent in aviation emissions. A report from the International Air Transport Association (IATA) noted that 2024 global SAF production hit 1 million metric tons, or roughly 1.3 billion liters. This represents just 0.3% of total aviation fuel and fell well short of earlier projections. Why?

Mixed signals from governments appear to be discouraging oil companies from fully committing to renewable fuels. Many of these companies can still benefit from subsidies aimed at fossil fuel exploration and extraction. Investors in SAF production want quick returns from their investments, something unlikely to happen in an increasingly uncertain market. The return of Donald Trump to the White House has undermined confidence in alternative fuels as a result of his rhetoric concerning increased exploration and drilling for oil and gas. If SAFs are going to have any impact on the race to stop +3°C, then production needs to ramp up dramatically before 2030 and that is unlikely to happen.

Another alternative is to use liquid hydrogen (LH2) as a fuel. It produces no CO2 when burnt but 2.5 times more energy per kg than kerosene (aviation fuel). It is quite simply a very clean fuel. Another useful feature of hydrogen is that it can be used as a replacement of liquid fuel or as a fuel cell for electrical power. Electrical fuel cells could be suitable for short-range aircraft while hydrogen combustion would be suitable for long-range and higher payloads. So why isn't it in wide use today?

Firstly, despite the aircraft needing a lower mass of fuel, any journey fueled by LH2 would require 4 times the volume of kerosene. This would require a complete redesign of conventional airframes.

Secondly, producing the enormous quantities of LH2 would present a very considerable challenge. Hydrogen is naturally found as a gas rather than a liquid, as it boils at -253°C, therefore, to transport it as a liquid it needs to be cooled or compressed. Since hydrogen is not naturally accessible in nature, it needs to be manufactured. Currently, the two main production processes use large amounts of electricity which is somewhat counter-productive.

Transport and storage of LH2 is subject to all manner of safety concerns given the flammability of the gas and the fact that it's odorless.

At some point in the next 30 years, these obstacles will be overcome and LH2 may well become the fuel of choice for long-haul aviation. That timescale is not quick enough, however, to stop +3°C.

Which brings me to the final solution, unquestionably the least popular but at the same time, the most effective and potentially immediate. Stop flying.

I have nurtured an ambition since I was a student to go climbing in Norway's Lofoten Islands, situated north of the Arctic circle on Norway's wild Atlantic coast. Flying distance from London to the Islands via Oslo = 3635 kilometers. CO2 footprint = 538kg x 2 (return) = 1076kg. That's over one tonne of CO2. I have four grandchildren ages 3 to 9. At some point in the next ten years when climate change invades every social media platform everyday, everywhere, my grandchildren will ask me when I gave up flying. "After all, Grandad, you were a science teacher, and would have known the carbon footprint of every long haul flight." They're smart, my grandchildren.

So am I flying to Lofoten? No. Driving in my electric car? No. Its carbon footprint for the journey is over 300kg. All that electricity has to come from somewhere and there's a lot of gas-fired power stations between London and the ferry to Oslo which are feeding a significant percentage of power to recharging stations.

My grandchildren are going to face the consequences of the rich nations' love affair with foreign travel. My love affair with foreign travel. Given the challenges posed by climate change that future generations will face, giving up flying is not much of a sacrifice. It won't save the world but it helps to salve my conscience.

Title photo: By Alan Wilson from Peterborough, Cambs, UK - Electroflight NXTE / Rolls-Royce ACCEL ‘G-NXTE’ “Spirit of Innovation”,