H Y D R O E L E C T R I C P O W E R

Fontana Dam, North Carolina,

From the Arctic regions of Greenland to the equatorial regions of Congo; from the largest countries - Russia, Canada and China - to the smallest Pacific archipelagos such as Fiji and Micronesia; even arid regions such as Mongolia or Tunisia: over 160 countries in the world generate electricity from water by means of hydropower plants. Hydropower currently generates around 17% of the world's electricity, making it the largest renewable energy source, with a total installed capacity exceeding 1,400 GW and producing approximately 4,200 TWh annually; this means hydropower produces more electricity than all other renewable sources combined.

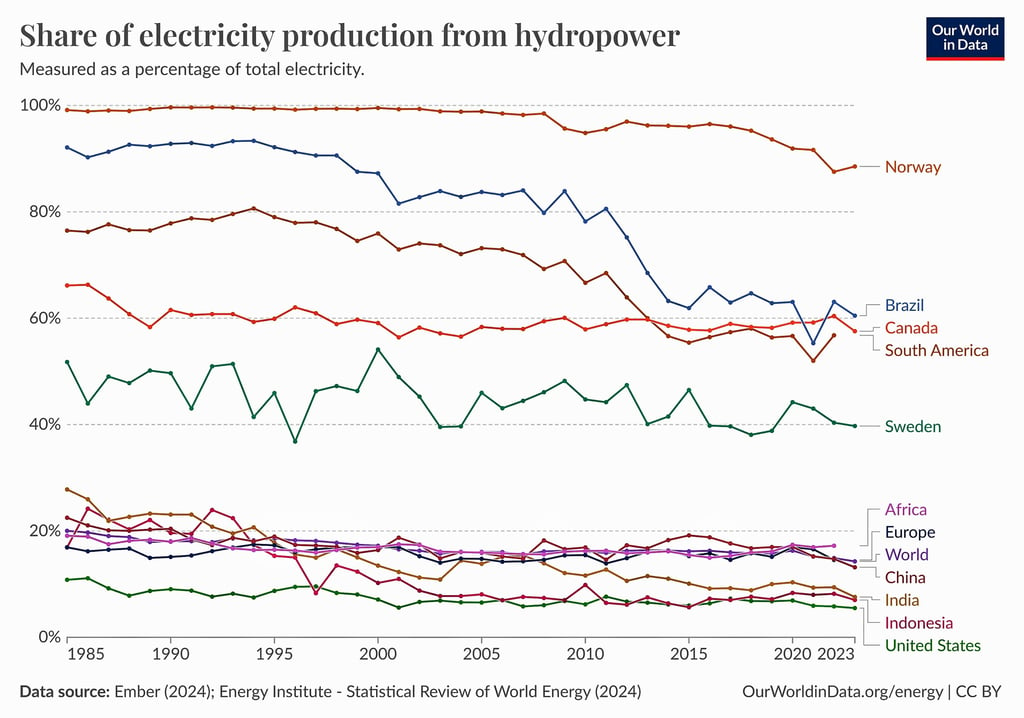

Figure 1

On the face of it, the hydropower picture looks bright. Growth in capacity is forecast to remain constant until 2030, driven by additions in China, India, Africa and Southeast Asia. Although hydropower generation is expected to increase globally as new projects become operational, the technology’s share in total power generation is expected to decline. The focus on solar and wind greatly exceeds that of hydropower. But to reach net zero by 2050, there has to be a doubling of capacity. Current forecasts based on power plants under construction and planning applications fall far short of this target.

Why should hydropower capacity increase when solar and wind farm capacity is growing almost exponentially? The answer lies in reliability. Solar and wind are termed 'variable renewables' with good reason. Hydropower is crucial for grid stability due to its ability to quickly adjust generation based on demand. Currently, countries around the world are turning back to fossil fuels to fill the gaps when the weather doesn't play ball. This cannot happen if the world is to get anywhere near net zero.

However, hydropower is not without its disadvantages.

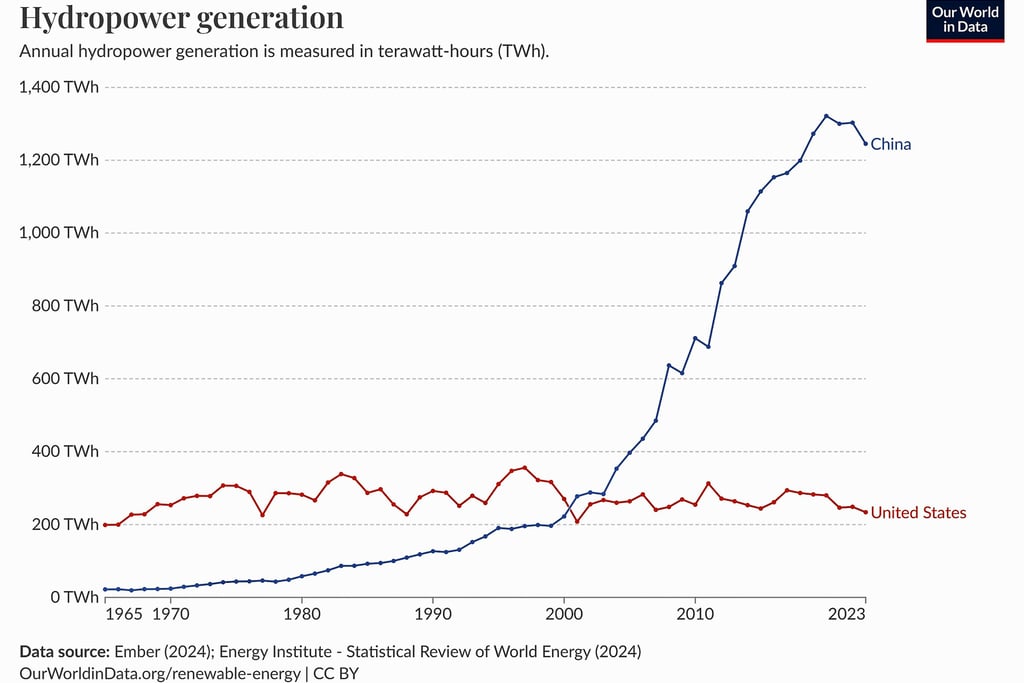

Take China, for example. It's the world's leading producer of hydropower, accounting for around 29% of the world's total. China's installed capacity of hydropower in 2024 was 426GW, more than five times the UK's total electricity generation capacity.

Hydropower is also China's largest renewable energy source. It continues to lead in terms of capacity additions, with 24 GW added in 2022, equal to three-quarters of all global growth. Hydropower remains an important part of the 14th Five-Year Plan for Renewable Energy released in 2022, but capacity additions are expected to slow down in the coming years due to a diminishing number of suitable sites and environmental constraints. And one of those constraints is drought.

Droughts drastically decrease the amount of water in rivers, meaning less water is available to turn turbines and generate electricity. Southwest China has been heavily affected since 2022. This region, with major rivers like the Yangtze, is a crucial source of hydropower, making it particularly vulnerable to drought impacts. Hydro generation has been essentially flat in China for the last three years (see figs. 1 and 2), despite commissioning several large new power plants. Since the drought started, the country has been forced to turn back to coal to meet electricity consumption, although increasing wind and solar capacity have helped meet some of the growth in demand. Some.

Figure 2

The US is the 3rd largest producer of hydroelectric power although it only accounts for 6.3% of its total electricity. It too is suffering from a drought problem. An article in The Verge (science, environment, climate) by Justine Calma entitled "Heat and drought are sucking US hydropower dry" reported on the riverflow crisis in the western US states:

'The amount of hydropower generated in the Western US last year was the lowest it’s been in more than two decades. [See Fig. 2] Hydropower generation in the region fell by 11 percent during the 2022–2023 water year compared to the year prior, according to preliminary data from the Energy Information Administration’s Electricity Data Browser — its lowest point since 2001.

That includes states west of the Dakotas and Texas, where 60 percent of the nation’s hydropower was generated. These also happen to be the states — including California, Nevada, Arizona, and New Mexico — that climate change is increasingly sucking dry. And in a reversal of fortunes, typically wetter states in the Northeast — normally powerhouses for hydropower generation — were the hardest hit. You can blame extreme heat and drought for the drop in hydropower last year.

This creates a vicious cycle:

Europe experienced a similar problem in 2022. Due to persistently high temperatures and scanty rainfall, some of the biggest hydropower operators in Europe, particularly those with facilities in France, Italy, and Spain, reported a sharp fall in production in the first half of 2022. The situation was critical in Italy, which generates one-fifth of its electricity from hydropower. The water flow in Serbia’s hydropower systems decreased by about a half, which increased the country’s dependence on the import of electricity.

Drought reduces the amount of clean energy available from hydroelectric dams. To avoid energy shortfalls, utilities wind up relying on fossil fuels to make up the difference. That leads to more greenhouse gas emissions causing climate change, which makes droughts worse.'

The other major environmental constraint in dam building for hydroelectric schemes is the loss of farmland, destruction of fish breeding habitats and worst of all, the displacement of communities. Prime Minister Wen Jiabao noted in a report to the National People's Congress in 2007 that dam building in China had displaced 23 million people over the years.

According to the International Energy Agency, while global hydropower capacity is expected to increase by 17% between 2021 and 2030, the rate of expansion is likely to slow down compared to previous decades, with the main growth occurring in regions like Africa, Asia Pacific, and the Middle East, as countries like China and Latin America see a slowdown in new hydropower projects due to limited viable sites and environmental concerns. However, as in 2021, the capacity added in 2022 was well below the estimated 30 GW of hydropower additions that are needed annually to keep global temperature rise below 2°C by 2050.

Put simply, if hydro construction is not ramped up, then +3°C looks increasingly likely.