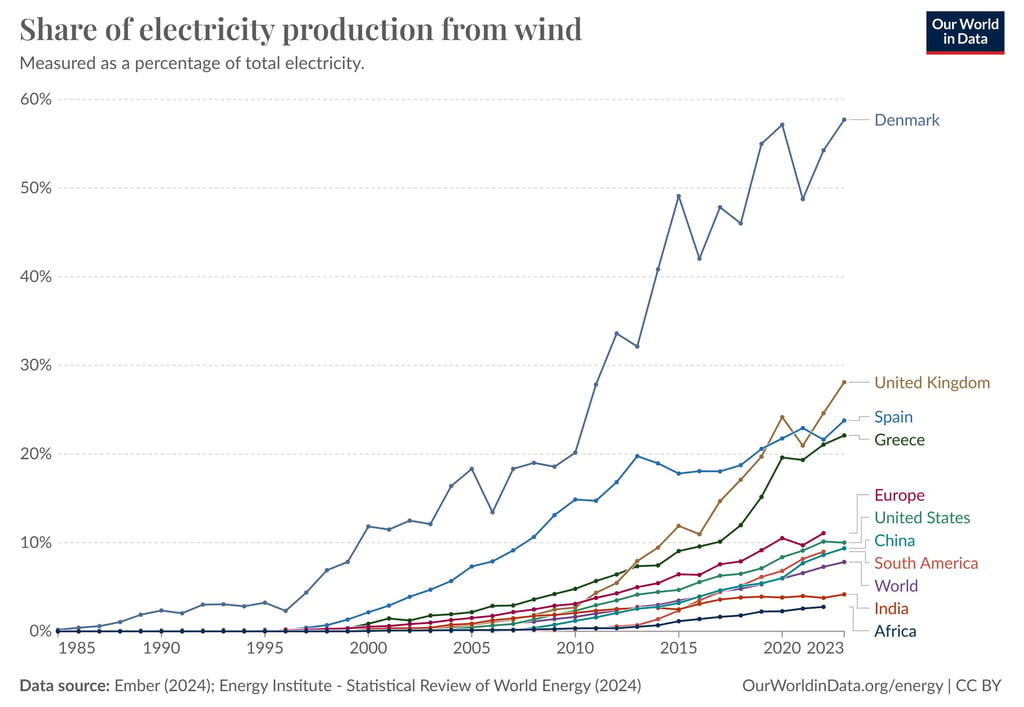

In 2022, wind power supplied 7.8% of the world's electricity. With about 100 GW added during 2021, mostly in China and the United States, global installed wind power capacity exceeded 800 GW. 32 countries generated more than a tenth of their electricity from wind power in 2023. Globally, the picture looks like this:

Figure 1

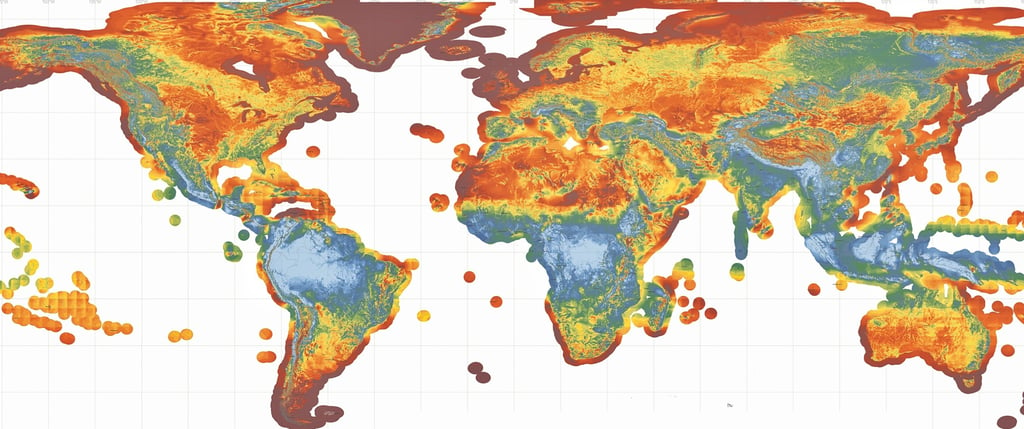

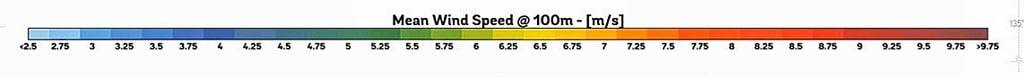

Of course, wind is not distributed evenly across the world. Fig.2 shows the global mean wind speeds around coasts and on land at a height of 100m above sea level.

Figure 2

It's clear that for countries in the tropics, wind power offers far less potential than around the coasts of northermost and southermost latitude countries. Denmark, projecting up into the windy junction of North and Baltic seas generates 57% (2023) of its electricity from the wind, a world-leading figure. Several other European countries - notably the UK, Germany and the Netherlands are tapping into the potential of wind with a number of huge offshore wind farms under construction or in the planning stages. The European Commission says Europe needs up to 450 GW of offshore wind by 2050, making it a crucial pillar in the energy mix together with onshore wind. 450 GW would meet 30% of Europe's electricity demand in 2050.

Looking at Fig. 2, it is obvious that South America has enormous potential for wind power, with countries like Brazil and Argentina leading the way in both onshore and offshore wind energy development. Estimates suggest there is over a terawatt (1000GW) of feasible capacity in each country. This is considerably more than the total current generating capacity of either country. With its vast coastal areas, strong winds, and favorable climatic conditions, Latin America could become a major wind energy powerhouse in the decades to come.

Australia is another southern hemisphere country with huge wind power potential around its coast. Rheinisch-Westfälische Elektrizitätswer (RWE), is a major player in the renewable market, building and managing solar and wind farms around the world. The Australian government has granted RWE a feasibility licence for the development of an offshore wind farm close to the Kent Group islands in the very windy Bass Strait, 67 kilometers off the coast of Victoria. This area is Australia’s first designated offshore wind zone and could provide electricity for 1.6 million homes. This will not be operational until the first half of the 2030s, too late to have an impact on Australia's 2030 emission targets.

And there lies the problem. Wind power is happening with projects in the pipeline all around the world but they are too little too late to achieve the UN 2030 emissions goal. Two contrasting countries illustrate the slow take-up of wind power:

Japan: Under increasing pressure to rein in its greenhouse gas emissions, Japan has developed a goal of becoming a major offshore wind power developer. The Japanese government recently increased targets for awarding contracts for offshore wind energy to 10 GW by 2030 and 30-45 GW by 2040. But in 2025, when time is fast running out to cut carbon emissions, wind power in Japan accounts for 0.9% of its electricity. In 2023, fossil fuels accounted for 69%.

In South Africa, just 5% of its electricity is generated by wind power, a small fraction of the wind power potential around South Africa's coast. It has plans to increase this but in the meantime, 85% of its electricity comes from coal-fired power stations. Coal is cheap; building wind farms is not.

Making plans, awarding licences, even contracts - these take years to come to fruition, before any electricity is generated. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), to reach net zero by 2050, global wind power capacity needs to significantly increase, reaching around 1,150 GW by 2050, requiring an average annual capacity addition of 350 GW by 2030, which is significantly higher than current levels; this means wind power generation needs to nearly quadruple to meet net zero goals.

http://www.cgpgrey.com, CC BY 2.0

The Middelgrunden offshore wind farm is located 3.5km from Copenhagen (Denmark) and consists of 20 turbines of 2MW each, producing up to 100,000 MWh of electricity annually