For some time now, natural gas has been considered a good stepping stone from coal to renewable energy. In many countries around the world, this is exactly what is happening. Gas is being used as a stand in for dirtier coal and oil while the transition is made to solar and wind turbines. After all, burning natural gas produces less carbon dioxide per unit of energy – about half compared to the best coal technology.

However, all is not as rosy as it first appeared. The main constituent of natural gas is methane. At almost every step in the gas journey from extraction to domestic or industrial combustion, leaks occur into the atmosphere. In addition, flaring of gas from wells is a widespread practice. In RMI's* article 'Reality Check: Natural Gas’s True Climate Risk', Deborah Gordon states that:

Over a 20-year period, methane is 84 times more potent as a greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide. There is yet to be a comprehensive policing program set up to detect and curb these gas leaks. 20 liquified natural gas terminals have been built since Russia invaded Ukraine to transport natural gas around the world and yet there is scant evidence available as to the extent of gas leakage from these terminals or the liquid gas tankers that use them.

Natural gas is not, therefore, as clean as once thought. Moreover, the speed of transition from coal through gas to renewables is also very variable around the world. It's a very brave, some would say foolish, economy that puts all its eggs in the renewable basket. The UK is a good example of a government which has closed all its coal-fired power stations in its move to renewable, the first G7 country to do so. Much has been made of the fact that in 2024, 58% of the UK's electricity came from low-carbon energy sources - wind, solar, biomass, hydro and nuclear, a truely creditable achievement. What was less well publicised is that 28% of the UK's electricity came from 49 gas-fired power stations. There's a lot of gas in the UK's energy basket.

*Rocky Mountain Institute climate think tank

As little as a 0.2% leakage of natural gas from rigs, pipelines, tankers and refineries elevates its global warming potential to that of coal.

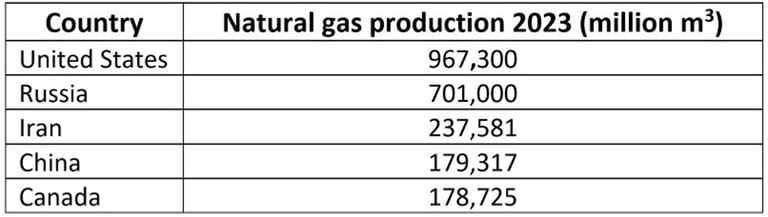

The big gas producers:

Table 1

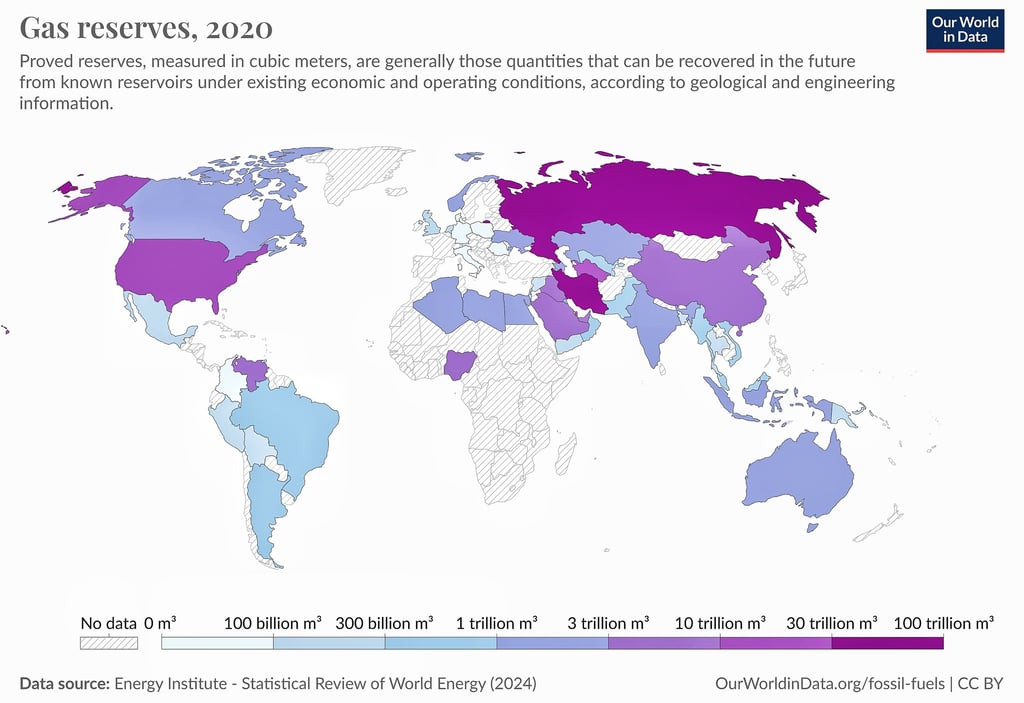

Gas reserves

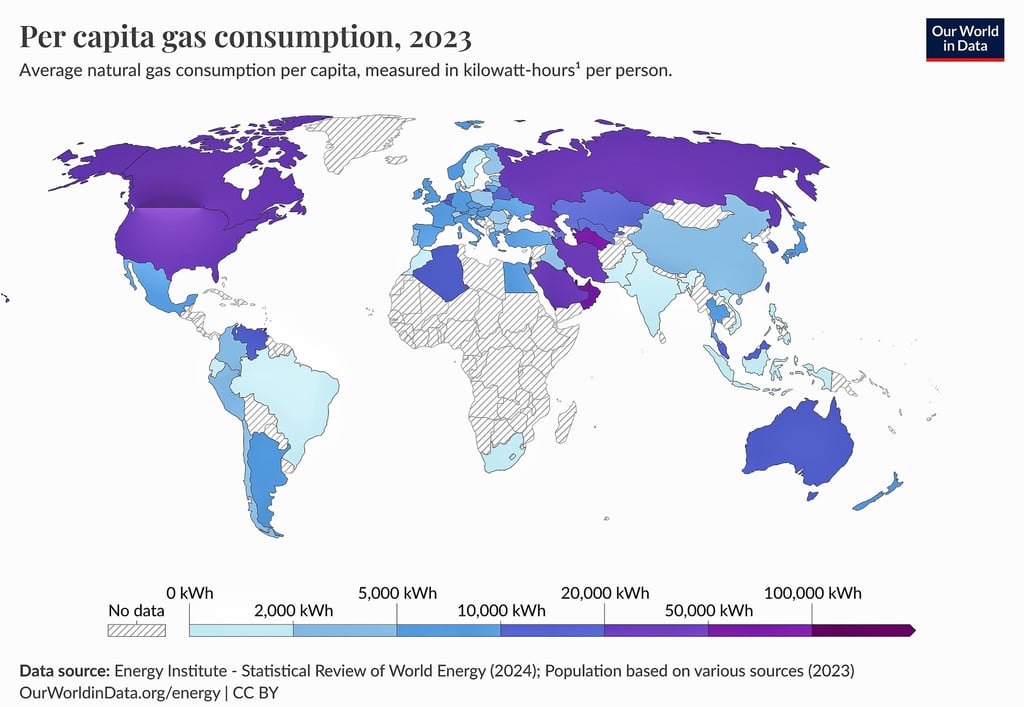

It's clear from the map below that there are still vast reservoirs of gas in the US, CIS (12 ex-USSR states) and Iran. Many countries across the globe see gas as a temporary (or not-so-temporary) substitute for their retiring coal industry, so there is little doubt that these reserves will be tapped adding a substantial amount of CO2 and methane to the atmosphere.

Figure 1

Gas consumers

Figure 2

An article in MIT's Climate Portal was written in response to the following question sent in by a concerned reader:

How much does natural gas contribute to climate change through CO2 emissions when the fuel is burned, and how much through methane leaks?'

"The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency estimates that about 6.5 million metric tons of methane leak from the oil and gas supply chain each year — around 1% of total natural gas production. At this rate, methane leaks would account for around 10% of natural gas’s contribution to climate change, and its CO2 emissions for the other 90%.

But other scientists have reported much larger figures for methane leaks. In a 2022 study focused on gas production in New Mexico, a group of Stanford researchers estimated that leaks equated to more than 9 percent of all production in the area, based on aerial surveys. A 2023 study suggested methane emissions were 70 percent higher than U.S. government figures from 2010 to 2019. Plata says there’s no current consensus on the magnitude of methane leaks.

“Leaks are so poorly quantified,” Plata says. “Nobody knows that number for sure. It's hard to sense methane comprehensively and finding those pipe-based leaks can be trickier than it sounds.”

Leaks can start and stop irregularly, in different places along the natural gas supply chain, making them hard to spot even as more methane-sensing satellites are put into space. For now, we’re largely dependent on scientists, industry, or citizen volunteers trying to find leaks one at a time, with equipment that is not consistently accurate."

The message is clear. Firstly, the gas industry must devote far more resources to curbing leaks. Secondly, every effort should be made to replace the gas stepping stone with renewables as soon as possible - 2030, not 2050. Every year that passes, gas adds millions of tonnes of CO2 equivalents to the climate change equation.