Title photo: As ice melts, the liquid water collects in depressions on the surface and deepens them, forming these melt ponds in the Arctic. These fresh water ponds are separated from the salty sea below and around it, until breaks in the ice merge the two.

Until recently, climate scientists have estimated that atmospheric warming in the Arctic was taking place between two and three times as quickly as the rest of the globe. However, in an article published in Nature in 2022, Mika Rantanen et al stated that the Arctic has warmed nearly four times faster than the rest of the globe since 1979. This estimate was based on the most recent observational datasets covering the Arctic region and illustrates the importance of using the very latest data to accurately assess the impact of GHGs on the climate.

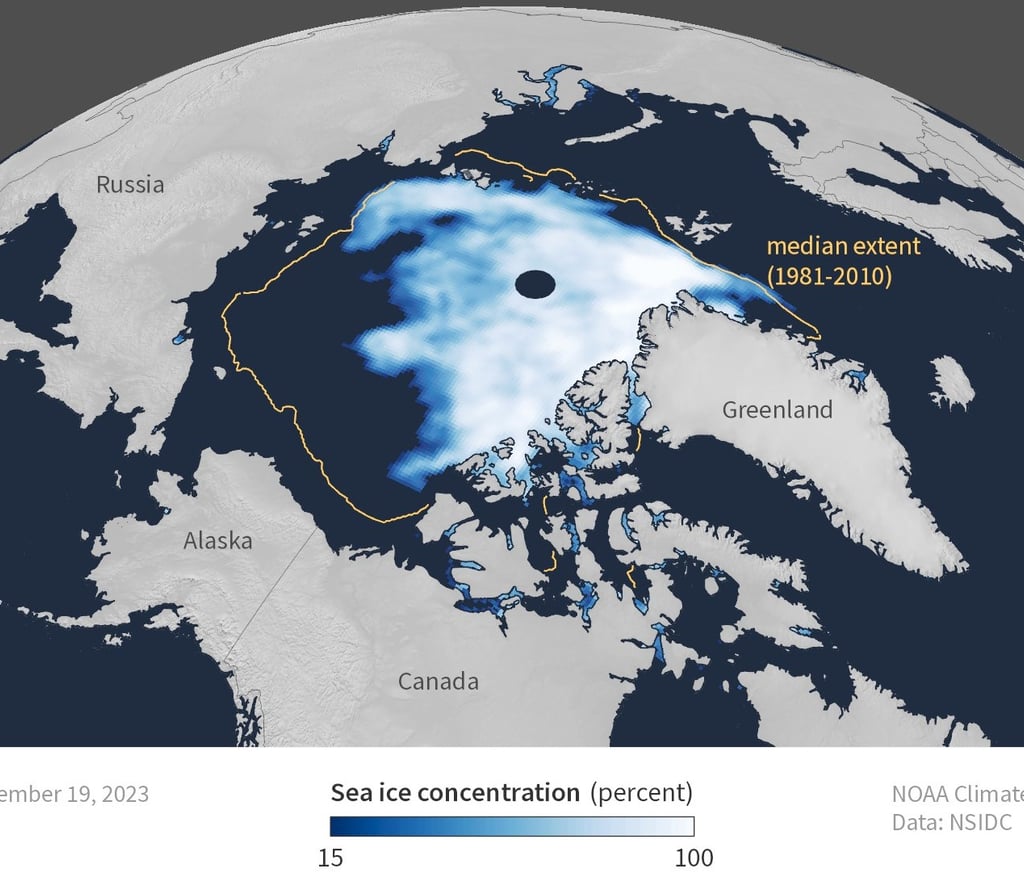

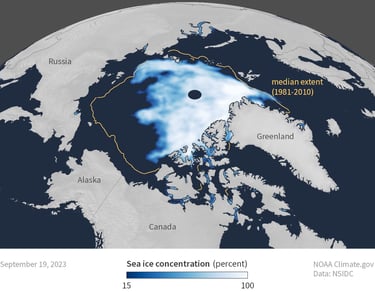

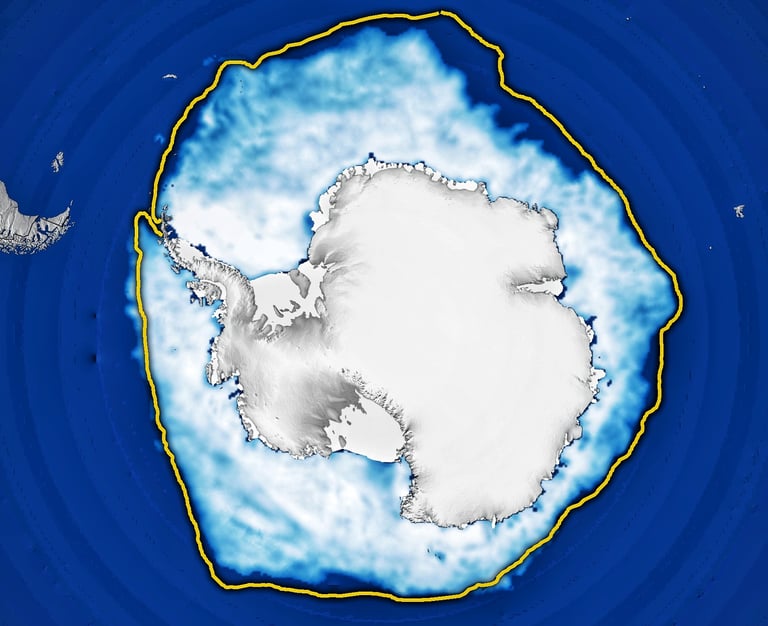

In the Rising Sea Level page, we looked at the impact of this warming on the Greenland ice sheet. Several generations of Homo sapiens will pass before it disappears completely, raising sea levels by 7 meters. That’s not something I will see, or my children and grandchildren even if the melting tipping point is reached before 2050. However, there’s a very good chance that my grandchildren, perhaps even my children will see the first cruise ship sail to the North Pole. The Greenland ice sheet is 1.6 kilometers thick on average. The Arctic ice pack is mostly around 3-4 meters thick and it’s melting rapidly. The map below shows the minimum extent of Arctic sea ice on 19th September, 2023 compared with the median extent in the years from 1981 to 2010 (orange line).

Arctic sea ice extent for September 19 2023, was 4.23 million square kilometers (1.63 million square miles). It was the sixth smallest summer minimum on record. The orange line shows the 1981 to 2010 average extent for that day. NOAA Climate.gov image, based on data from the National Snow and Ice Data Center.

If ever there was an image which summarised the rapid melt of Arctic sea ice, this is surely it.

Or perhaps Figure 2 takes the 'image impact' prize.

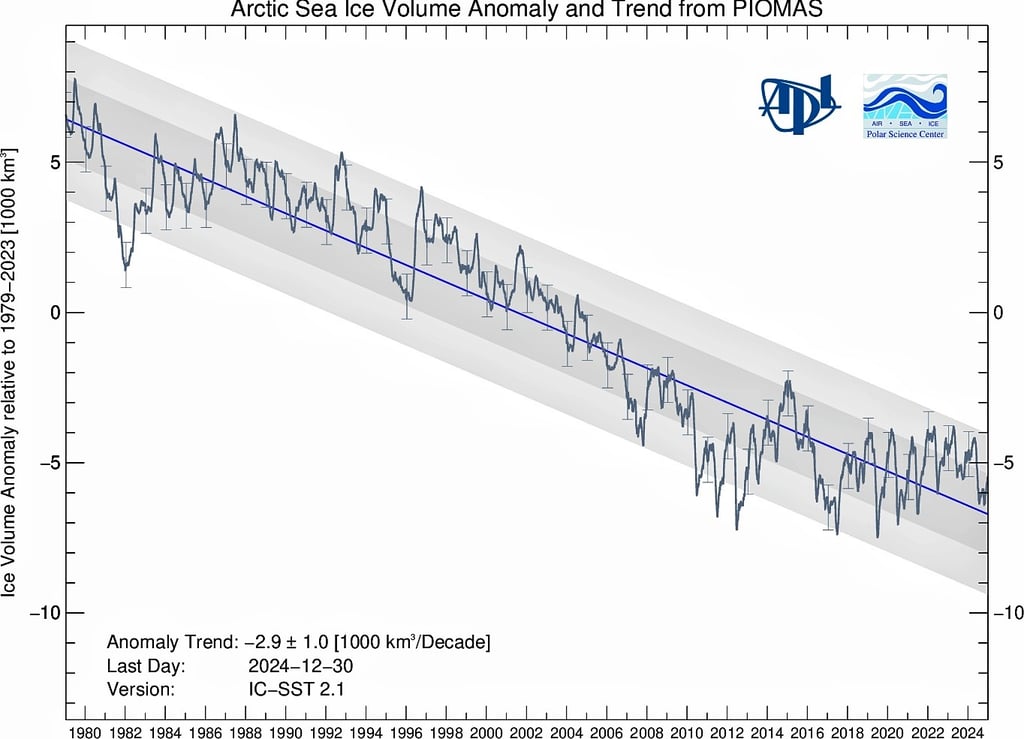

Figure 1

Welcome to PIOMAS, the Pan-Arctic Ice Ocean Modeling and Assimilation System. Stay with me. This highly advanced program has been developed in conjunction with the Polar Science Center (PSC), part of the Applied Physics Department at the University of Washington. The PSC has been collecting a vast quantity of data concerning Arctic ice thickness and area and, using PIOMAS, calculating the total Arctic sea ice volume. This is what their software came up with.

Arctic sea ice volume anomaly from PIOMAS updated once a month. Daily Sea Ice volume anomalies for each day are computed relative to the 1979 to 2023 average for that day of the year. The trend for the period 1979- present is shown in blue.

There has been much discussion in the media over the apparent stall in the decrease of Arctic sea ice since around 2012. This stall is clearly seen in the graph above. Let's for the moment ignore the blue trend line, a human device to create long term average ice loss. Look back at 1981 to 1982. Arctic sea ice volume fell by over 5000km3 to a new historic low. Then over the subsequent years to 1988, its September low (Arctic ice is always at its minimum in September) recovered. The mistake is to treat fluctuations over a small number of years as trends. Those working at the Polar Science Center have deliberately plotted a trend line (blue) through the fluctuations (something you'll see in almost every climate graph) in order to neutralise them, and the blue line is falling.

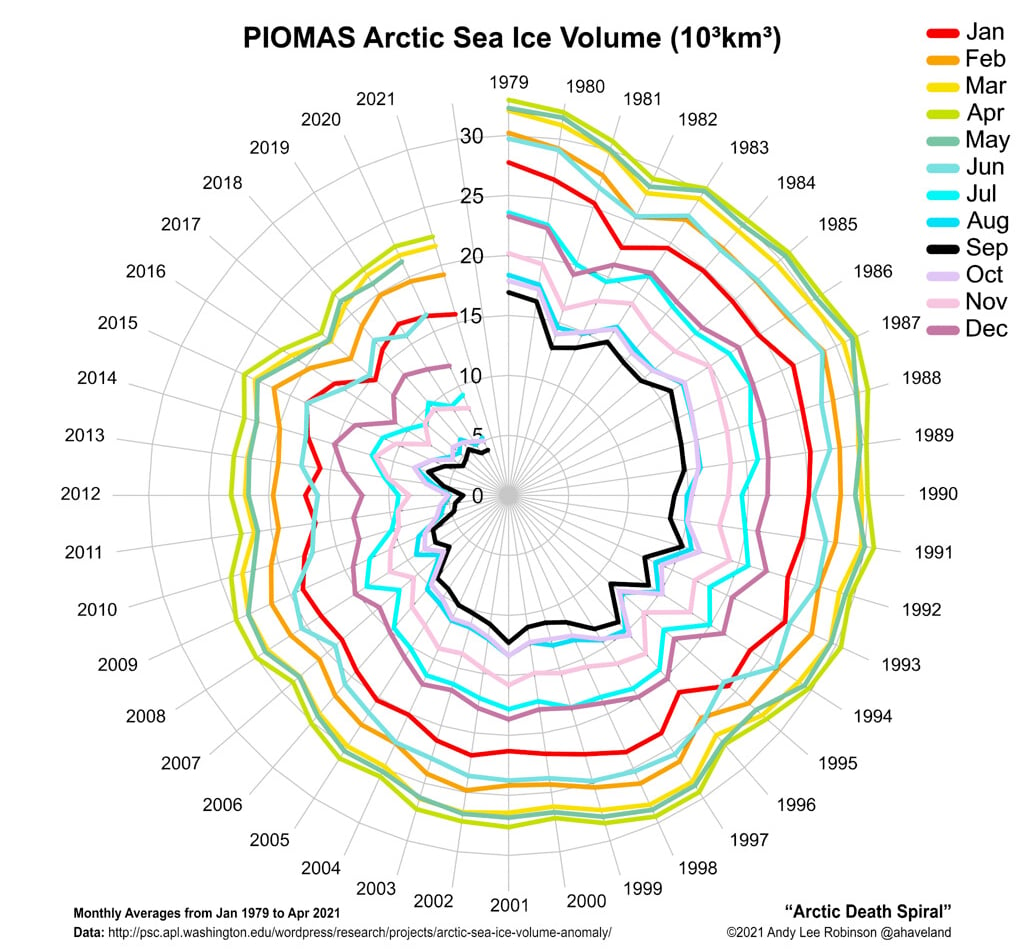

An alternative method of plotting PIOMAS data, one that displays monthly variation in ice volume is shown below. It's another powerful expression of the melting trend. Look at the black line (September values) from 2014 to 2020. There is no mistaking the fall in September minimum Arctic ice volume over these years.

Figure 2

Finally – the Arctic sea ice tipping point. The more the ice melts, the more quickly the remaining ice melts. The reason for this lies in a single word – albedo. Albedo (from Latin albedo 'whiteness') is the fraction of sunlight that is reflected by a body. Albedo measures from 0 for a black object which reflects no light at all to 1 for an object reflecting 100% light. On Planet Earth, freshly laid asphalt has an albedo of 0.04 while for fresh snow it's 0.9. So why does albedo matter? If Earth were frozen and entirely covered with snow and ice, it would reflect almost all sunlight and with it, heat. The average temperature of the planet would drop below −40 °C.

In contrast, if the entire Earth was covered by water (dark, non-reflective), the average temperature on the planet would rise to almost 27 °C. Albedo matters, more today than it ever has because Arctic ice with its albedo of 0.9 reflects a lot of light and keeps the entire planet at just the right cool temperature. Or it used to in 1900. 13.7°C. Since then, two factors have combined to raise that average temperature up to 15.1°C:

global warming due to greenhouse gases;

the gradual fall in Earth's albedo. Currently it's 0.3. That is too low to keep the Earth at 13.7°C.

Melting sea ice, ice caps and glaciers; deforestation; urbanisation - all these processes make the Earth darker and lower albedo. The Earth warms. As Arctic sea ice melts, the ocean absorbs more solar radiation and heats up. This causes more sea ice to melt and the ocean warms still further. Scientists call this Arctic Amplification and it is happening at a frightening rate right now.

Figure 3

Right now, Arctic sea ice is the youngest and thinnest it's been since records were first kept. More than 70% of Arctic sea ice is now seasonal, which means it grows in the winter to a thickness of around 2 meters and melts in the summer. It doesn't last from year to year. This seasonal ice melts faster and breaks up more easily, making it much more susceptible to wind and atmospheric conditions, in other words weather.

What has become clear in the last few years is that what remains of the thick, permanent ice will take many years to melt, possibly not this century. Maybe reaching the North Pole by boat is something I won’t see if it requires thick, old ice to melt around it.

It is, however, the 70% of seasonal ice that is of far greater concern. Indigenous peoples living in the Arctic depend on sea ice for travel, fishing, hunting, and protection of their vulnerable coastlines. Each September, vast swathes of the Arctic become completely ice-free. This is bad news, not only for local people, but also for the wildlife that depends on the ice.

Figure 4

Fig. 4: Narwhals used to use sea ice as a protection against predators but now killer whales are showing up in large numbers, hunting narwhals which, without the ice, are easy prey.

Figure 5

Fig. 5: Sea ice gives polar bears access to seals which hide their young beneath the ice. When ice forms late or is too thin for seals to make their dens, food becomes scarce and polar bears run the risk of starvation during summer months.

Figure 6

Fig. 6: Pacific walruses prefer to spend their time on ice in groups known as haul-outs. It’s here they socialize, rest and reproduce. This ice-based habitat also provides access to food. When sea ice shrinks or melts entirely, it forces walruses to haul out on land in huge numbers where food availability is severely limited.

Figure 7

Fig. 7: Arctic caribou are known for their epic long-distance migrations so it’s no surprise ice serves as a migratory habitat for some caribou in the North. Two populations found high in Canada’s North, Peary caribou and the Dolphin and Union herd, are completely reliant on sea ice for their migrations. The absence of sea ice would be disastrous for these groups, completely disrupting their migrations. Less reliable sea ice that is thin or forms later in the year could result in a population decline for both groups.

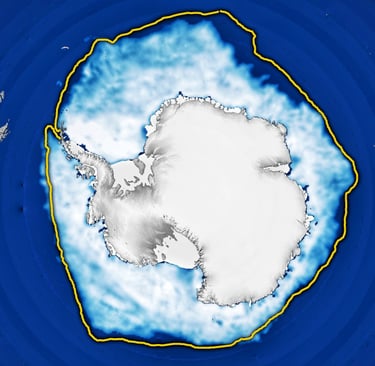

The winter sea ice around Antarctica covers an area of some 18.5 million km2, 3 million km2 greater than winter Arctic sea ice. In the past, climate scientists have been puzzled as to whether the winter Antarctic sea ice maximum was shrinking or growing year by year. Now there is little doubt that it's shrinking.

Figure 8

The 2024 winter maximum, shown in Fig. 4 above, was the second lowest in the satellite record, remaining just above the record winter low of 16.96 million km2 set in September 2023. The average maximum extent between 1981 and 2010 was 18.71 million km2 shown by the yellow line.

The meager growth in 2024 prolongs a recent downward trend. Prior to 2014, sea ice in the Antarctic was increasing slightly by about 1 percent per decade. Following a spike in 2014, ice growth has fallen dramatically. Scientists are working to understand the cause of this reversal. The recurring loss hints at a long-term shift in conditions in the Southern Ocean, likely resulting from global climate change.

“While changes in sea ice have been dramatic in the Arctic over several decades, Antarctic sea ice was relatively stable. But that has changed,” said Walt Meier, a sea ice scientist at NSIDC. “It appears that global warming has come to the Southern Ocean.”

Just how quickly the winter sea ice area shrinks is unknown. While it won't contribute to sea level rise, the sea ice does impede the disintegration of the Antarctic ice sheet and that certainly will impact on sea level.

The 2024 winter maximum, shown in Fig. 4 above, was the second lowest in the satellite record, remaining just above the record winter low of 16.96 million km2 set in September 2023. The average maximum extent between 1981 and 2010 was 18.71 million km2 shown by the yellow line.

The meager growth in 2024 prolongs a recent downward trend. Prior to 2014, sea ice in the Antarctic was increasing slightly by about 1 percent per decade. Following a spike in 2014, ice growth has fallen dramatically. Scientists are working to understand the cause of this reversal. The recurring loss hints at a long-term shift in conditions in the Southern Ocean, likely resulting from global climate change.

“While changes in sea ice have been dramatic in the Arctic over several decades, Antarctic sea ice was relatively stable. But that has changed,” said Walt Meier, a sea ice scientist at NSIDC. “It appears that global warming has come to the Southern Ocean.”

Just how quickly the winter sea ice area shrinks is unknown. While it won't contribute to sea level rise, the sea ice does impede the disintegration of the Antarctic ice sheet and that certainly will impact on sea level.