Photo by Filippos Sdralias on Unsplash. Varnavas, Greece, 2009.

W I L D F I R E S

Message from Filippos Sdralias, the photographer: The photo above is taken in 2009, when a huge wildfire started [in Greece] in August. I wish none to experience a destructive wildfire. The memories won’t be good, I promise you. However, there is something I noticed and I would like to mention. There are some heroes who save life and properties working under very difficult conditions, risking their life. There are not enough words to thank them.

I am writing this section of the website in mid-January, 2025. Starting on January 7th, wildfires ravaged the Los Angeles area, displacing tens of thousands of people, destroying at least 12,000 homes and businesses and claiming at least 25 lives (as of Jan. 15th) The Palisades fire was the first to erupt. Thus far, it has burned its way through 23,700 acres. At the time of writing, it is still burning with only 18% containment (the percentage of its perimeter which cannot spread further.) The Eaton fire started a few hours later, devastating 14,100 acres including the residential area of Altadena. It too is still burning (Jan. 16th) with 35% containment. These two fires alone (there were 10 other lesser fires) rank among the deadliest and most destructive in Californian history. I am sure that all those reading this would echo Filippos Sdralias' message above to the men and women who put their lives on the line daily all around the world to prevent loss of life from the growing number of wildfires.

Which brings us to the key question. Is climate change to blame for the increased frequency, ferocity and duration of wildfires around the world?

The Los Angeles fires provide stark evidence that climate change is playing a role in increasing the risk of wildfires. Having said that, California has a history of wildfires going back hundreds, if not thousands of years. It has been estimated that prior to 1850, about 4.5 million acres burned yearly, in fires that lasted for months, with wildfire activity peaking roughly every 30 years, when up to 11.8 million acres of land burned.

The California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection keep accurate records of every wildfire in the State. Looking through their records of (1) the 20 largest wildfires, (2) the 20 deadliest wildfires, and (3) the 20 most destructive wildfires, not one of these fires took place in January. Not one. Most of the fires took place from July through to November. In fact, just six wildfires have burned more than 1200 acres in any January in California since 1984. Six January fires in 40 years. So why this year? And why on this scale?

Figure 1

Palisades Fire as seen from Downtown Los Angeles

Figure 2

Erickson Aero Tanker MD87 Fire Bomber dropping fire retardant on the south slopes of the San Gabriel Mountains to prevent the spread of the Eaton Fire

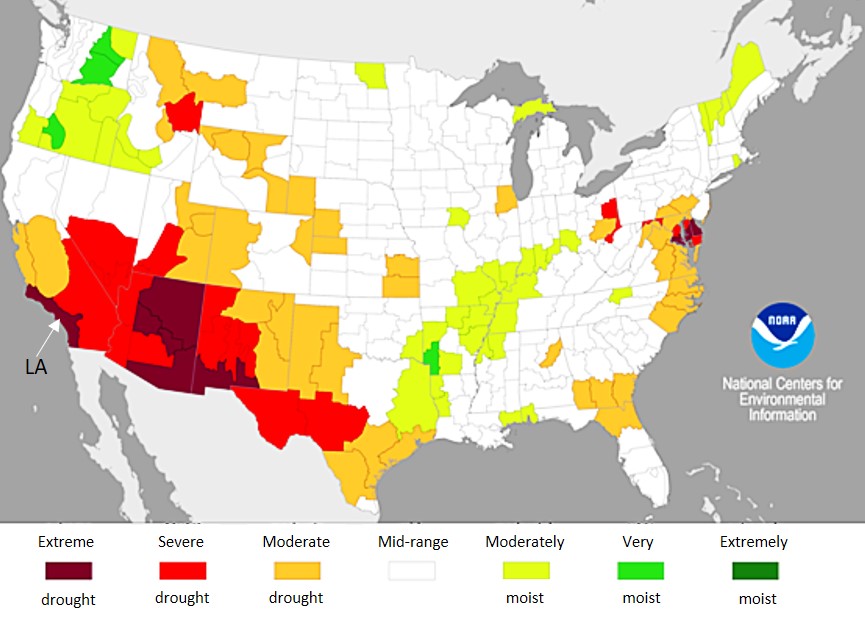

The 2025 Los Angeles fires have been described as the consequence of the perfect storm, the coming together of three factors whose combination in January resulted in such tragedy. The first is displayed clearly in the December 2024 drought map of the USA below with Los Angeles (LA) marked.

National Centers for Environmental Information, Annual 2024 Drought Report

Figure 3

2024 was the US's warmest year on record. Grace Toohey, a Staff Writer for the Los Angeles Times wrote on Jan. 4, 2025, just 3 days before fire broke out:

"California is entering the fourth month of what is typically the rainy season, but in the Southland, the landscape is beginning to show signs of drought.

The last time Los Angeles recorded rainfall over a tenth of an inch — the threshold that officials typically consider helpful for thirsty plants and the reduction of wildfire risk — was May 5, when downtown received just 0.13 inches of rain.

"It’s safe to say this is [one of] the top ten driest starts to our rainy season on record,” said Ryan Kittell in January 2025, a National Weather Service meteorologist in Oxnard. “Basically, all the plants are as dry as they normally are in October. Typically we see, at this time of year, close to 4 inches of rain, which would usually be enough to squash any significant fire weather concerns,” Kittell said. “But because we haven’t had anything close to that, and because we’ve had a really active two years [of plant growth] ... there’s a lot to burn.”

The really active two years that Kittell is referring to was the result of an exceptionally wet winter 2023 and spring 2024. This led to the growth of an extraordinary new vegetation biomass in the hills surrounding the city. Factor number 2. The drought conditions which followed turned all this vegetation into fire fuel.

Just three days later, wildfires broke out. California is well used to such fires. However, the third factor, the Santa Ana winds, turned bushfires into raging firestorms. The Santa Ana winds blow westward from the cool interior down the steep mountain slopes across the city to the warmer sea. In 2025, they were driven by very strong winds in the upper atmosphere.

In an article on the Los Angeles fires in the World Resources Institute on January 14, 2025, James MacCarthy and Jessica Richter wrote:

"The increasing frequency and intensity of wildfires in California can be attributed to a combination of natural and human-induced factors, with climate change playing a central role. Rising global temperatures have created hotter, drier conditions across the landscape. This makes fires not only more likely to ignite but also easier to spread."

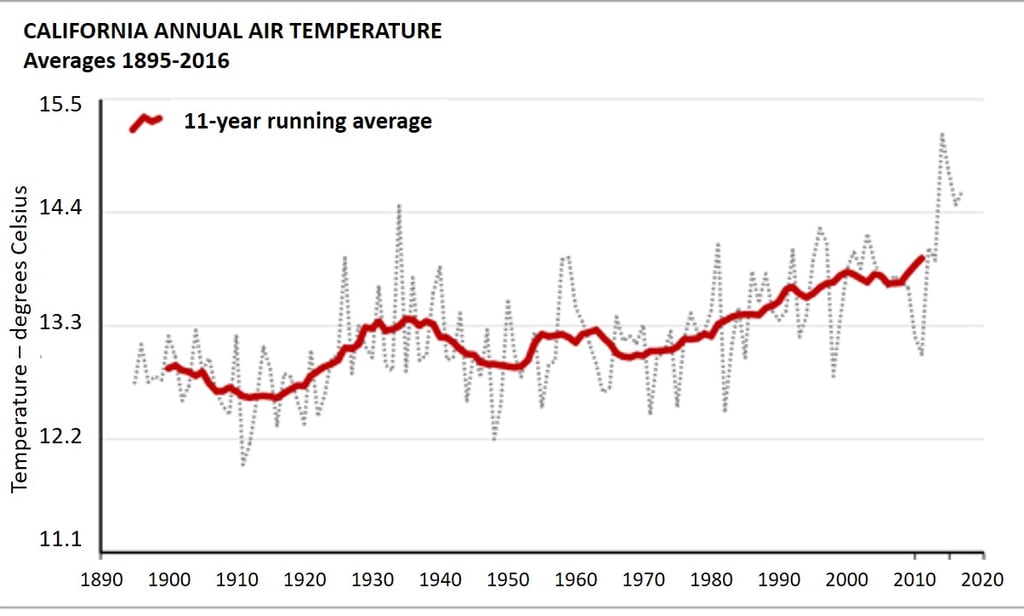

It is too early to draw hard and fast conclusions about the role of climate change in the LA fires, but it is looking highly likely that when the Extreme Weather Attribution work has been done, the finger will point in that direction. With California air temperatures rising inexorably since the 1960s (see below) and winter rainfall in southern California increasingly unreliable, winter wildfires may become more frequent.

California Environmental Protection Agency

Figure 4

By RCraig09 - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=139008417

What is happening in California is being replicated throughout the world. The chart below shows the number of worldwide wildfires which claimed the lives of at least 10 people or affected over 100 people.

Alarmingly, forest fires now account for 33% of tree cover loss compared with just 20% in 2001. Global forest fires are becoming ever more frequent with 2020, 2021 and 2023 being the 4th, 3rd and 1st worst years for such fires.

The 2023 forest fires in Canada made national headlines around the world and for good reason. They accounted for about two thirds (65%) of the fire-driven tree cover loss that year and more than one-quarter (27%) of all tree cover loss globally. In an article in Global Change Biology, James MacCarthy et al. writes:

Extreme heat and low rainfall associated with climate change led to unprecedented forest fires that released enormous amounts of carbon as they burned.

Extreme heat, low rainfall - a lethal combination. 7.8 million hectares of forest were burnt. That was bad enough but of greater concern was the 3 billion tonnes of CO2 emitted from the fires into the atmosphere. Two points of note:

First, total global energy-related CO2 emissions for 2023 were 37 billion tonnes.

Second, emissions from these wildfires will have been largely* (see below) excluded from official greenhouse gas reporting.

3 billion tonnes of CO2 is nearly 4 times the carbon emissions of the entire global aviation sector in 2022.

Figure 5

....the area burned by forest fires increased by about 5.4% on average per year between 2001 to 2023. They estimate that, each year, there is almost 6 million more hectares of forest burnt today than in 2001.

In a World Resources Institute article titled The Latest Data Confirms: Forest Fires Are Getting Worse, James MacCarthy et al., calculated that....

More and more focus is being directed at forests in the northermost latitudes - the boreal or taiga forests - given that they act as one of the Earth's largest sinks for human-produced CO2. 30% of all trees on the planet are in the boreal biome - between 50 and 70 degrees north - which spreads across Canada, China, Finland, Japan, Norway (Fig.6), Russia, Sweden and Alaska covering an area of 17 million square kilometers, 14% of Earth's land and 33% of its forest. Global warming here is happening at least twice as fast as the rest of the planet. As a result, boreal forests are growing faster than ever before, taking in more CO2 from the atmosphere. Surely this is welcome news. In the short term it may be, but boreal forest has not evolved to live in such warm conditions, nor such dry conditions. Moreover, as we pointed out earlier, warm and dry is a lethal combination which results in greater frequency, intensity, duration and spread of forest fires. The more fire, the greater the CO2 emissions.

Figure 6

Northern boreal forest in Dividalen valley, Norway

However, recent research into carbon emissions from boreal forest fires has discovered a serious oversight regarding the origins and quantities of CO2 released in these fires. Research Associate Stefano Potter from Woodwell Climate reported that the overwhelming majority of carbon emissions from boreal fires—over 80% of total emissions in most places—comes from soils rather than trees. Despite the dramatic imagery of burning forests, most of the real damage is happening below the ground. The below-ground burning is being left out of existing global fire and climate models, which means, Stefano Potter says, we’re drastically underestimating carbon emissions from Arctic and Boreal environments.

*Under guidelines from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, countries can designate a portion of their lands as “unmanaged,” under the assumption that they are not subject to direct human influence and are thus not the focus of Paris Agreement goals to limit human-induced greenhouse gas emissions. While not all countries apply this “managed land proxy” (Ogle et al., 2018), Canada designates roughly 30% of its forest area as unmanaged and is not subject to reporting.